Beauty and Science

What is beauty?

This is the first of a series of blog entries with the following sub-title: "How do I convince my 12-year old daughter that scientists are not all nerds without any sense of fashion (her words, no offence meant)"? Ever since she made that comment, I have been meaning to write on this topic. Here's my first attempt.

Recently I came across a TED talk by Dr Anjan Chatterjee entitled "How your brain decide what is beautiful". Dr Chatterjee makes a convincing case for a Darwinian theory of beauty (which I will refer from now on as canonical beauty) based on three main cardinal points: averaging, symmetry and level of hormones. According to this theory, features that are attractive are those that are most likely sought and passed on from one generation to the next by natural (sexual) selection. Moreover, the human brain has evolved into paying beauty a lot of attention, even at the unconscious level. According to Dr Chatterjee, when a random set of people were shown pictures of different individuals with the aim at recognizing faces, most of the cerebral activity recorded in the study participants was around "beautiful" faces. Moreover, there is often an association of beauty with goodness, a concept already expressed by the Greeks with their "kalos kai agathos" (beautiful and good) concept. I believe this is hardly under dispute. What struck me most though was what he said at the end of the talk: people that considered beautiful get better jobs, are generally paid better (not sure this applies to women across the board), receive less punishment and are considered more capable and worthy than less attractive people.

This may be true in general, but then I thought about my daughter's comment: in science being beautiful might actually be a disadvantage. Here's why.

The face of a scientist

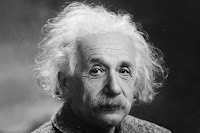

If I showed anybody these two pictures, one of famous scientist Albert Einstein (left) and the other of likewise famous pop singer Ariana Grande (below), I bet you any money that 99% of the people would say that the older man with messy hair is a scientist whereas the young girl with long luscious hair is definitely not. My point here is that in our age of images we have come to associate the face of a scientist with that of a senior man. Far from me to dispute the fact that Einstein may very well have been attractive in his own right and that he himself spent most of his life in pursuit of the beautiful symmetry of the law of physics, but surely his is hardly a face in which a 12-year old girl can recognize herself (unlike Ariana's). Of course, I went to the extreme and used an iconographic scientist and an iconographic pop singer. But the point remains that there is a stereotypical notion embedded in our culture that to be a scientist one should not care about looks and should not be a canonical beauty. The stereotype is so strong that it goes beyond the gender boundaries to the point that even male scientist who are good-looking are met with a lot of suspicion by their peers and by society in general. Basically scientists cannot be beautiful according to Dr Chatterjee's canonical definition, or if they are, they cannot be good at science.

Science: is it a girl thing?

A few years ago, the European Commission ran a campaign called "Science: it's a girl thing" in an attempt to increase the number of young women in Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) disciplines. The testimonial video featured extremely good-looking young women in high heels, with heavy make-up and glasses, surrounded by molecules and circuits. The official video was taken down shortly after an out-pour of criticism from the scientific community, outraged at the fact that it misrepresented the profession and reinforced stereotypes about what young women should like or look like (see for example, an interview with astronomer Dr Meghan Gray and an article in the Guardian by professor Curt Rice).

The irony is that in this example the Beauty Myth is completely reversed but still used against women. Author Naomi Wolf argues that beauty is the "last, best belief system that keeps male dominance intact". In the workplace, she writes, women are often valued or judged according to their physical appearance rather than their performance, even in jobs where physical attractiveness is not part of the requisites. In science, the opposite is true. The more beautiful a woman is, the less she is considered capable of being good at science or being even able to perform rational thinking. How many jokes are there about "stupid blondes"?. For sure, everybody would agree that there is no scientific proof of a correlation between a person's intelligence and the colour of their hair. In a way, the EU campaign was trying to challenge that very stereotype, unfortunately playing straight into the hands of the misogynist narrative, so that young girls interested in science might have taken home the message that they had to be as good-looking and fashionable as the women portrayed in the video (possibly professional actresses and models) to have a chance in a science career, on top of being good at maths and physics. Of course we do not know that as I am not sure the target audience was ever consulted on the matter.

How do we fix this?

There is no easy solution. The first step is to bring awareness regarding the stereotypes that we all carry with us. Being aware of our (unconscious) biases brings us closer to being able to challenge them. The second step is to keep an open mind: you don't know where you are going to find the next Einstein and whether she/he will have moustache and messy hair or a tidy pony-tail and perfect teeth. The third, and most important, step is to get school-age children acquainted with inspirational scientists of all walks of life to show them that the faces of scientists are as varied as the faces of the entire world population.

That, and possibly convince Ariana Grande to give up her career as a pop star, get a degree in one of the STEM disciplines and become a testimonial for the sciences. It is possible that a lot of young people would be then inspired in considering science as a career option.

This is the first of a series of blog entries with the following sub-title: "How do I convince my 12-year old daughter that scientists are not all nerds without any sense of fashion (her words, no offence meant)"? Ever since she made that comment, I have been meaning to write on this topic. Here's my first attempt.

Recently I came across a TED talk by Dr Anjan Chatterjee entitled "How your brain decide what is beautiful". Dr Chatterjee makes a convincing case for a Darwinian theory of beauty (which I will refer from now on as canonical beauty) based on three main cardinal points: averaging, symmetry and level of hormones. According to this theory, features that are attractive are those that are most likely sought and passed on from one generation to the next by natural (sexual) selection. Moreover, the human brain has evolved into paying beauty a lot of attention, even at the unconscious level. According to Dr Chatterjee, when a random set of people were shown pictures of different individuals with the aim at recognizing faces, most of the cerebral activity recorded in the study participants was around "beautiful" faces. Moreover, there is often an association of beauty with goodness, a concept already expressed by the Greeks with their "kalos kai agathos" (beautiful and good) concept. I believe this is hardly under dispute. What struck me most though was what he said at the end of the talk: people that considered beautiful get better jobs, are generally paid better (not sure this applies to women across the board), receive less punishment and are considered more capable and worthy than less attractive people.

This may be true in general, but then I thought about my daughter's comment: in science being beautiful might actually be a disadvantage. Here's why.

The face of a scientist

|

Image credits. Creator:Getty Images

Credit:Dave Hogan for One Love Manchester

Copyright:2017 Getty Images

|

Science: is it a girl thing?

A few years ago, the European Commission ran a campaign called "Science: it's a girl thing" in an attempt to increase the number of young women in Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) disciplines. The testimonial video featured extremely good-looking young women in high heels, with heavy make-up and glasses, surrounded by molecules and circuits. The official video was taken down shortly after an out-pour of criticism from the scientific community, outraged at the fact that it misrepresented the profession and reinforced stereotypes about what young women should like or look like (see for example, an interview with astronomer Dr Meghan Gray and an article in the Guardian by professor Curt Rice).

The irony is that in this example the Beauty Myth is completely reversed but still used against women. Author Naomi Wolf argues that beauty is the "last, best belief system that keeps male dominance intact". In the workplace, she writes, women are often valued or judged according to their physical appearance rather than their performance, even in jobs where physical attractiveness is not part of the requisites. In science, the opposite is true. The more beautiful a woman is, the less she is considered capable of being good at science or being even able to perform rational thinking. How many jokes are there about "stupid blondes"?. For sure, everybody would agree that there is no scientific proof of a correlation between a person's intelligence and the colour of their hair. In a way, the EU campaign was trying to challenge that very stereotype, unfortunately playing straight into the hands of the misogynist narrative, so that young girls interested in science might have taken home the message that they had to be as good-looking and fashionable as the women portrayed in the video (possibly professional actresses and models) to have a chance in a science career, on top of being good at maths and physics. Of course we do not know that as I am not sure the target audience was ever consulted on the matter.

How do we fix this?

There is no easy solution. The first step is to bring awareness regarding the stereotypes that we all carry with us. Being aware of our (unconscious) biases brings us closer to being able to challenge them. The second step is to keep an open mind: you don't know where you are going to find the next Einstein and whether she/he will have moustache and messy hair or a tidy pony-tail and perfect teeth. The third, and most important, step is to get school-age children acquainted with inspirational scientists of all walks of life to show them that the faces of scientists are as varied as the faces of the entire world population.

That, and possibly convince Ariana Grande to give up her career as a pop star, get a degree in one of the STEM disciplines and become a testimonial for the sciences. It is possible that a lot of young people would be then inspired in considering science as a career option.

Comments

Post a Comment